This Guest Post is by Jon Buerg. I’ve known Jon for many years through the ARCHICAD community in Minnesota. You probably know him from his previous blog post about Bruce Lee and BIM. I am constantly inspired by his vision, leadership, and application of BIM. The challenges he faces and conquers with his work at Wilkus Architects provide so many great lessons, especially for those of us doing greatly different project types.

George Nelson’s “How To See” is the perfect design criteria for life.

Are you in charge of development for a chain that’s looking to roll out your concept across multiple locations? If yes, sweet! If no, carry on. I am an architect who has been on the receiving end of design criteria from dozens of organizations like yours for the better part of the last two decades. I’ve seen the good, the comically bad and the downright awful. The great news is doing design criteria right is easier than you think. Here’s how:

Part 1: What the hell are you talking about with this “design criteria”?

Design criteria is the content that your organization creates to convey the design intent for your concept to the consulting architects and engineers that are hired to design individual locations for your chain concept around the region, country or world. Sometimes you’ll hear design criteria referred to as a CD set, a template, a design manual, specs or drawings. This chain concept slang is inaccurate and a part of why so many chains get this stuff so wrong.

Part 2: Why do I need design criteria?

If you’re laughing out loud at this question, it’s all good. Please proceed to Part 3. For the rest of you, design criteria does the following for you (when it’s done well, that is):

- Ensures consistent compliance with your organization’s current brand and design image

- Enables your consulting architects and their engineers to save time, and time is money

- Provides a consistent baseline for evaluating development costs over time (both soft costs and hard costs)

- Reduces change orders from contractors and provides more consistent construction costs from location to location

- Provides an efficient system for communicating change from your organization out to your consulting architects, engineers and contractors

Part 3: Great, I’m sold. Now, who should do this work in my organization? And more importantly, who should not do this stuff?

You need your own architect that is internal to your organization to do what I’ll explain below. Why? Because this is design, and design doesn’t just mean all the pretty pictures you see when you look at architectural drawings. Design in this context also means to design the system of documentation and content as well as the delivery system for that documentation and content in order to ensure that the consulting architects you hire will be able to carry out your vision successfully on a repeat basis. Design also means to organize design criteria and maintain that organization over time for the rollout of your concept so that the criteria are always clearly communicated and current with your organization’s latest thinking. There’s one more aspect of design that is important here. Your architect will need to hire a good consulting engineer that she can coordinate design criteria for the engineers that’ll be working on the rollout, and I’ll elaborate on that later.

Architects are the great generalists of the project team and also the only members of the project team who possess the skill set necessary to pull this off well. Notice the word “well”, plenty of other people can fuck this up. That architects are so well versed in all aspects of the project delivery cycle is also why they can be excellent leaders for your organization’s entire development group-but that’s something to elaborate on in another article another time.

What’s bad? Thinking your construction staff should lead this effort. The construction folks should be kept busy developing the systems and documentation that’ll lead to quality bids from great contractors and also to put in place processes for continually assessing the work being constructed for conformance to the criteria. The construction department should be empowered to provide feedback to the design department about what’s working or not working out in the field. Don’t worry; your talented internal architect knows to reach out to your entire development department to solicit their thoughts on how this should go, as well as their feedback on what she creates for your organization’s design criteria. This is a family effort and your internal architect is the head of household.

Part 4: What don’t the consulting architects need? Probably most of what you would think they do need.

The consulting architects (and their consulting engineers for that matter) do not-I repeat DO NOT-need a complete CD set of your prototypical design, and if they’re telling you that they do, these are totally the wrong people to be doing your work because they just plan stamp the thing, collect a fee and check out. Then the project goes to permitting, bidding and construction, and everyone will be pissed because things will be going so shitty; and they’ll be shitty because the consulting architect didn’t take the time to get to know the design criteria because you prepared this CD set to the nth degree and that sent them into autopilot.

On top of that, when you develop a CD set, you’re also putting your own drafting standards into that document and then handing it off to a consulting architect who has to depart from their own firm’s drafting standards to try and navigate through your CD set-and that alone can increase the probability for errors and omissions. I can’t emphasize enough how toxic it can be to your mission to burden your consulting architects with a complete CD set. Think about it, ideally you want to engage consulting architects for the long term because that gives you the advantage of really getting to know each other well and those relationships are the ingredient to great outcomes. Part of the foundation of this relationship is you empowering the consulting architect to be just that, an architect, and to determine the best way to document your concept.

Right about now, the construction folks in your organization, and perhaps other departments too, will be freaking out super hard. They’ll tell you that consistency of documentation between different architecture consultants working around the region/country/world on your rollout is key to success, in part because it helps them carry out their mission, which is to manage the bidding and construction phases of project delivery. They’re absolutely correct about this. Then they’ll say that’s exactly why you need to develop a complete set of construction drawings. They’re absolutely wrong about that. All that’s needed is an outline of content for each deliverable document and/or drawing package your organization wants your consulting architects to produce for you. That way, every consulting architect’s deliverables match up in terms of what piece of information is located where. Everyone can relax now. More on this outline stuff in Part 5…

Part 5: The list of stuff you need to give your consulting architects for a successful rollout.

Part 5: The list of stuff you need to give your consulting architects for a successful rollout.

- Detailed outlines of each deliverable you require from the consulting architects and engineers.

These outlines should give names and numbers to sheets as well as what content goes on which sheet. They should also include information on page sizes and scales for particular drawing content. For non-drawing deliverables, the outlines should provide enough detail to guide the consultant through creation of that particular document-think of the outlines we got for making reports in school-that sort of thing.

- A standard title block in DXF format with everything in a single pen color on a single layer.

This format allows any consultant to bring your standard title block into whatever software platform they want to use and still have it look uniform. It’s important for you to standardize your title block as it contains a lot of important information that your organization will use to organize all the projects that will be developed in your rollout. Item 3 on this list is also a key ingredient of this title block as it impacts appearance of the title block.

- A collection of your organization’s graphic design content and criteria.

What specifically am I talking about here? Go to your graphic designer and have him prepare a folder full of the font files and vector artwork that makes up your brand’s image. The vector artwork should be converted in to DXF files and further purged of layers and colors. We’ll also need a version of that vector artwork in an open format based on the original, full-color version and I would suggest a PDF file. We’ll also want a list of colors used in this brand imagery and conveyed in Pantone numbers, an equivalent color management system, or RGB values. Lastly, we’ll need a copy of the graphic design criteria that your designers use to guide usage, placement, sizing, etc. of the various graphic elements.

- Any standard details that are prototypical to the design in DXF format with everything in a single pen color on a single layer.

Just like the title block, this is an open format that allows your consultants to quickly import your standard details into their software of choice. You’ll want one DXF file for each detail.

- Any standard specification content in RTF format.

Your specifications need to be in MasterFormat and that combined with using RTF format allows you to be open, so your consultants can bring those specifications with all their formatting (indents, numbered lists, etc.) into whatever software they choose for their workflows and also allows for your specifications to easily mesh with those of the consultants.

- A design guide in PDF format.*

A good design guide can be the bridge between taking a consultant who is unfamiliar with your organization’s concept and making that consultant into someone who is ready to carry out that concepts’ identity. The process of creating a design guide will be a challenging one, as it requires a keen understanding of the basic nature of your concept, as well as a discipline in getting to the point with concise writing and easy to follow graphics to explain ideas. The very act of developing and maintaining a design guide over time is an excellent way of keeping your concept in check and staying true to your roots.

- Standard finishes, fixtures and equipment data.

By data, I mean several things:

- Cut sheets for each standard fixture and piece of equipment in PDF format, with one individual PDF for each item and a file name with the name of the piece as well as it’s standard identification number to be used in the construction documents. (Your standard identification numbers for each finish, fixture and equipment piece should be included in the outline I describe in item 1 of this list, as well as what information about these things you want to appear in schedules.)

- A repeatable pattern image file in PNG format for each standard finish and a file name with the name of the finish as well as it’s standard identification number to be used in the construction documents. (The specifics of what these standard finishes are should appear in the appropriate specification sections that I mention in item 5 of this list.)

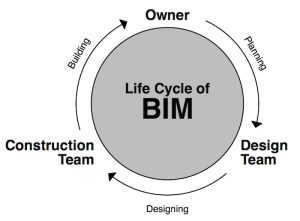

- A single IFC 2 x 3 file for each fixture and piece of equipment that contains a complete three dimensional BIM of the item as well as embedded IFC data for the item’s information that you want to see scheduled in the construction documents (such as manufacturer, model, installation responsibilities, utility rough-in information, etc.) and a file name with the name of the item and it’s standard identification number to be used in the construction documents.

- Engineering criteria in PDF format.

Perhaps your organization has standard engineering criteria: a certain type of diffuser you use, a preference for joist girders for long spans, maybe you like plumbing supply piping to be a specific material for some reason, or you want to make sure that your IT systems are protected by certain equipment in the electrical supply. Gather up all this information into engineering criteria that are organized by engineering discipline.

* Design guides can be a controversial topic. The argument against them is that they instantly become outdated, and thereby become both ineffective and cumbersome to maintain. I argue this is because they’re too detailed. A good design guide is just like good design, simple and refined. It needs to focus on its purpose, which is to clearly and concisely state the mantra, the dogma, the rules of the road, the whatever-you-want-to-call-it that guides the principals of your concept’s design. Your consulting architects should be able to get through the design guide in 60-minutes or less, they should enjoy reviewing it, and it should become a resource that they return to over time. If your organization’s design guide is as thick as the phone book, includes details and is bloated with mundane crap like what sheen of paint should be used where, throw it out and start over. Detailed information like that belongs elsewhere; this is a high level document.

Part 6: That’s a fair amount of information, how do we manage it?

Great question! First, this is the 21st century and this information needs to live in The Cloud, where both your organization and your consultants can get to it and where the information gets updated automatically as it changes over time. And that leads me to my next point: managing change.

Since your organization will undoubtedly need to change, add on, take away or otherwise alter something in that list above, you need a system for organizing and communicating that change to your consulting architects, engineers, vendors and contractors. Let your organization’s internal architect take the lead here and develop that system. She will compile the data that makes up the change and speak with the stakeholders about timing and urgency behind the change. Then she will communicate that change out to all the various consultants by explaining: what, why, when and how. Before issuing the change, she will also make sure everything in that list under Part 5 that is affected by the change has been updated as well. The most important part of managing change tends to be the management of when to implement the change in the midst of a rollout where there are often dozens or more projects that are all in different phases of development. There will be lots of opinions in your organization about how to decide on this aspect of the change and you all need to trust your internal architect to listen to those opinions and formulate a measured response.

PS – Concerning The Cloud, don’t use some proprietary solution that requires everyone to install some lamebrain software just to be able to see the files residing in The Cloud. Keep it simple and web browser based.

Part 7: Wait, I have a prototypical building as a part of my concept’s rollout!

Oh, umm…Okay. I was trying to get out of here without discussing that. But I guess it’s the reality we deal with, right? So here it goes. Get rid of your proto-building, let’s be bold! No, just kidding. If you have a prototypical building design, have your internal architect first model that building in its entirety as a three dimensional BIM in IFC 2 x 3 file format. More specifically, here’s how to break down that BIM based on some common scenarios:

- If you have multiple options for interior build-out versus shell design, keep each shell and each interior in separate IFC 2 x 3 files

- If you use different methods of envelope construction depending on geographic region, economic model or for any other reason, keep those different envelopes in separate IFC 2 x 3 files

- Keep the BIM simple, at least in the beginning, as assembling a BIM can be a very personal thing for each consultant. Keeping the BIM simple will make it easier for the consultants to adjust to their own needs

- This is a starting point, your internal architect, with input from the consultants will be able to tweak the base models she provides over time for improved efficiency and reduced errors

Part 8: Don’t rush it…yet.

There’s a lot of pressure from all sorts of people in your organization with a vested interest in seeing this rollout get going yesterday and then blazing along at a breakneck pace. You’re going to be hiring consulting architects to carry out the design of this rollout using all of this great new design criteria that you’ve carefully created and the biggest mistake you could make at this point in the process is to rush those new consultants into their first project. I know. I know. We don’t have time to dawdle around here, and that is precisely why we must not rush things! Both you and the consulting architects are interested in a long-term relationship. For you, it’s so you don’t have to waste time and money training consultants every time you have a new project. For the consulting architect, it’s so they don’t have to run up costs training staff on a new client for every new project they’re hired to design. There’s a mutual interest in getting things off to a good start here.

Your internal architect will be able to establish a program to onboard new consulting architects and a timeframe for getting those architects ready for their first project. Often, this can be as simple as providing some extra time and hands on guidance for the first project. Another important part of this training process is for the team to get together at the end of that first project to discuss what worked, what didn’t work and how to make that better next time. Architects value these kind of relationships and go the extra mile to perform for clients who take the time to get the project delivery process right. That means this initial investment of time will pay dividends in the form of smooth-running rollouts that are able to stay on schedule — and maybe even reduce schedule over the course of the rollout. Your organization should value that kind of payback.

Now, rollout!

As promised, there’s the good, the comically bad and the downright awful truth about chain concept rollout. It may seem like a lot, but this is a smaller and easier to manage list than what I’ve seen from many of the concepts I’ve been exposed to over the years. You can do this!

Subscribe to the blog so that you don’t miss future guest posts from Jon Buerg: Shoegnome on Facebook, Twitter, and the RSS feed. You should also go ahead and follow Jon on twitter. Hopefully that will encourage him to share more of his thoughts on BIM and being an architect in the 21st century. Jon and I first met at an ARCHICAD user group. If you liked this post, let Jon know and then go attend a user group meeting.